- The Remarkable Forgotten History of Thunderbird 1 - Feb 23, 2020

- Ghosts of WWII – Phoenix Airfields Beneath our Feet - Oct 5, 2019

- The Dutchman: Part 3: Glenn Magill & the Last Great Discovery - Mar 10, 2019

Note: This is part 2 of a three-part series introducing Arizona’s most famous legend, the Lost Dutchman Mine. In Part 1, the elderly, dying Dutchman, Jacob Waltz, told his caretaker Julia Thomas he was awarded a rich mine deep in the Superstition Mountains for service to the Peralta family of Mexico, and abandoned it when his partner was killed by Apaches. Julia said Waltz told her how to find the mine in October 1891, and left her gold ore worth $1200 as proof. Please enjoy and feel free to comment and share!

Part 2: Julia Thomas

Julia Thomas must have been a commanding figure. She was just 29 when she set out for the Superstitions with the Petrasch brothers, two German miners she recruited for the job. It is remarkable enough that a woman of color in post-frontier Phoenix had the strength and leadership ability to organize and bankroll an expedition of hard-bitten miners and burros and lead them directly into terrain so unforgiving it kills people even today. That she did it in the humidity and heat of August is practically unbelievable. Julia Thomas was apparently capable of it all.

Incredibly, the trio survived three weeks in the Superstitions wilderness, eventually forced out by lack of water- exhausted, and with no gold.

Newspaper reports of her trek (Julia seems to have had a knack for attracting media) made her even better known in Phoenix, but she was out of money. She peddled Dutchman maps for cash and sold her story to a San Francisco Chronicle reporter, who published the first comprehensive account of the Lost Dutchman in 1893.

There is no record she ever owned a business after this, and she was clearly never the same.

She divorced Emil Thomas – who she said abandoned her – and married Albert Schaeffer, a hay bailer. Newspapers report she and Albert invented a religion, a blend of Judaism and Christianity that became popular with local Native Americans. The charismatic Julia turned up in Tucson in 1900, preaching to the Tohono O’odham. Albert appeared before the Phoenix City Council in 1913 claiming that “the Almighty God, Jehovah” wanted him to have a tax exemption for their adobe house at 137 W. Jackson Street. The papers noted the pair kept perpetually burning fire pits on their property and practiced “strange” rites.

The marriage to Albert reportedly failed, and when Julia died in 1917 at just 55, she was described as destitute. Interestingly, she was buried in Phoenix’ original Jewish cemetery. She has no descendants, and there are no photographs or other depictions of Julia.

Her grave is lost.

Adolph Ruth and the Peralta Maps

Almost 40 years after Julia Thomas’ fruitless trek, Adolph Ruth became the next well-known victim of the Dutchman legend. A retired government worker and amateur treasure hunter, Adolph Ruth had a son, Dr. Erwin Ruth, who was a federal veterinarian in Texas in the nineteen-teens, inspecting cattle the Woodrow Wilson administration was buying from cross-border rebels to help finance the Mexican Revolution. The story goes that Dr. Ruth got up to his neck in dangerous politics, and at one time managed to extricate former Mexican consul to the US Pedro Gonzalez from some difficulty. When Ruth mentioned his father collected western lore and old maps, Gonzalez, a cousin of the Peraltas, arranged for Ruth to receive three maps to an old Peralta mine in Arizona – presumably as mementos, not as keys to fabulous riches.

Another fanciful tale? Maybe.

But Pedro Gonzalez is a historical figure and was present in Texas and the Gulf Coast cities during his career. He was frequently in political danger and was ultimately executed by the Huerta regime in Mexico City in 1914.

And Erwin Ruth did give maps to his father.

Adolph Ruth needed years to understand them. Unlike traditional aerial views, the Peralta maps consisted of profiles of mountain ridges as seen from a specific perspective, mismatched scales, and other confusing elements. One was even a mirror image of the scene depicted. They seemed to have been made so that only the original author could use them.

It was not until May 1931 that the 66-year-old Ruth, hampered by a bad leg suffered on a treasure quest in California, arrived in Apache Junction from Washington, DC. Despite the blistering heat, he immediately made plans to enter the mountains. He told everyone he had a map that would take him straight to the mine and was eager to start.

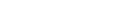

Apache Junction rancher Tex Barkley warned Ruth repeatedly of the danger, suggesting he wait until autumn’s cooler conditions, but Ruth was adamant. Reluctantly, Barkley assigned two employees to pack Ruth into the Superstitions. In late May, 1931, they led Ruth deep into the mountains, leaving him in Needle Canyon with a promise to return with more supplies. When they came back ten days later, Ruth had disappeared.

Dr. Erwin Ruth flew to Arizona and led a high-profile search for his father, featuring a plane and photographer supplied by the Arizona Republic. But there was no sign of him. It was not until December that a hound dog attached to an archeological survey team found Ruth’s skull above Needle Canyon, across from Bluff Springs Mountain, on Black Top Mesa, with two holes in it, one on each side.

In a bizarre coincidence, the dog’s owner was George “Brownie” Holmes, son of Richard Holmes, the man present with Julia Thomas at Jacob Waltz’ deathbed. The archeologists were accompanied by a photographer, so there are excellent documentary photos of the grisly find.

Tex Barkley himself found the rest of Ruth’s remains in January 1932, miles from where his skull was discovered. In Ruth’s clothing was his checkbook and inside, a handwritten note: “About 200 feet across from the cave.” Further down, written separately, were the words “Veni. Vidi. Vici.”

I came. I saw. I conquered.

Searchers recovered Ruth’s personal effects with one exception – his maps.

Despite the evidence, including the fact that Ruth had not fired his gun, his death was ruled a suicide. More practical people suspected he had been murdered for his maps, possibly by the cowhands who escorted him, but no one was ever charged.