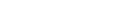

- Fountain Hills Ties as Safest Zip Code in Phoenix - Oct 14, 2019

- How Many Single-Family Homes in Maricopa County? - Oct 13, 2019

- Investing in Multi-Family Real Estate in Your 20s - Oct 9, 2019

A trivial scrap metal sale for $8.50 in a Mexican border town morphed into one of the largest radiation spills in U.S. history. The November 1983 junkyard transaction has an uncomfortably intimate connection to the Phoenix housing market across the border, but details of the event have been largely forgotten.

I came across the story recently while sifting through the 1984 archives at The Arizona Republic.

Three and a half decades ago, 600 tons of radioactive steel stock from Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua rolled through a customs checkpoint in El Paso, Texas on several trucks. Customs lacked radiation detection equipment and they were approved to enter. Before the loads were intercepted, the irradiated steel flowed northward into 28 U.S. states. Within weeks, the steel would be used in residential and commercial construction projects in Arizona.

Authorities were first alerted to the presence of the radioactivity when a truck hauling a load of the steel made a wrong turn near the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and set off radiation alarms. Officials on both sides of the border scrambled to understand and contain the spill.

Here is how the pieces came together, beginning with 1960s-era medical equipment from Texas.

It started in Lubbock

A secondhand U.S.-made Picker 3000 radiation device that was developed to combat cancer was sold to a medical clinic in Ciudad Juárez in 1977. Representatives for the Mexican health clinic later claimed they never had the resources to hire someone to operate the cancer therapy machine. As a result, it sat for many years mothballed in a storage facility south of the border. That fact alone is tragic enough.

In November 1983, it was removed from storage by a local electrician, Vicente Sotelo, and a co-worker. Mr. Sotelo reported that he was authorized to retrieve and sell the items in the warehouse for scrap metal. The clinic’s doctors disputed the claim.

Too Hot to Handle

The Picker 3000 was torn apart on Mr. Sotelo’s truck and cut up with a torch. The main capsule contained 6,010 small 1-milimeter pellets of Cobalt-60, resembling silver cake decorations. Cobalt-60 is a radioactive isotope used to target tumor tissue in cancer treatment. It is also known as Gamma Knife therapy.

Th pellets spilled in the back of Mr. Sotelo’s pickup truck and onto the road as he made his way to the Jonke Fenix scrapyard in Ciudad Juárez. Some of the radioactive pellets were later found to have melted into the pavement of the roadway along the route. The contaminated truck continued to emit high levels of radiation.

The tainted pickup truck would later sit unattended for weeks in Mr. Sotelo’s neighborhood with a flat tire while children played in and around the truck bed.

According to a New York Times article from 1984, a health physicist at the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Agency estimated that each of the pellets produced 25 rads of exposure if it was within 2 inches of an individual. A rad is a measure of radiation. By contrast, a passerby exposed at the Three Mile Island incident would have only been exposed to 1/10 rad or 1/250 of the amount of radiation from the Ciudad Juárez spill.

Mr. Sotelo sold the dismantled medical device for scrap metal and pieces were strewn throughout the junkyard by an overhead magnet. The scrap was then delivered to a nearby foundry for processing. The foundry melted the metal down and formed it into steel reinforcement bar, or rebar, as well as metal restaurant table legs.

Rebar of varying lengths is incorporated in wet concrete to add rigidity after the concrete is cured. In residential home construction, rebar is commonly used to reinforce concrete in slab foundations, block wall and swimming pool construction.

Arizona Exposure

In a January 26, 1984 article in The Arizona Republic, state Radiation Regulatory Agency deputy director Richard Blanton reported that the radioactive Mexican rebar had been traced to new construction at private Arizona residences. Providentially, most of the contaminated rebar was still stacked at construction supply yards or job sites and had not yet reached large numbers of builders or homeowners.

Some of the radioactive rebar was found in Wickenburg where a resident had constructed an eight-foot tall block wall that was 114-foot in length. Yet more was found inside internal walls of 6 Quonset huts on the grounds of the Arizona State Prison Complex in Florence. A third site with the contaminated rebar was discovered in Mesa at the Baywood Medical Complex on South Power Rd.

A few of the radioactive table legs found their way into Phoenix restaurants including a Sun City diner and an Arby’s at 24th St. and Thomas Rd. They were dismantled in 1984 and returned to Mexico for disposal.

South of the Border

The impact of the radiation spill was much worse in Mexico. Hundreds of inhabitants of Ciudad Juárez became nauseated and exhibited symptoms of radiation poisoning. Chromosome testing on several of its residents indicated radiation damage at the cellular level. Fingernails of many of the junkyard employees turned black.

In the western state of Sinaloa, 200 homes that contained the rebar were condemned by Mexican authorities and were torn down.

One year after the spill, authorities concluded that they had recovered all of the contaminated steel after sweeping both sides of the border with detection equipment and meticulously analyzing shipping logs. The rebar and table legs were collected and returned to Mexico where the government buried the radioactive waste.

It is a story that illustrates the butterfly effect of how a small, singular, insignificant event can ripple to potentially affect hundreds of thousands of individuals with unintended consequences.

Each year, at the typical nuclear reactor in the U.S., there’s a 1 in 74,176 chance of an earthquake strong enough to cause damage to the reactor’s core, which could expose the public to radiation. No tsunami required.

– Bill Dedman, American journalist and author of Empty Mansions, a #1 New York Times Bestseller about the life of Huguette Clark, reclusive daughter of Jerome, Arizona copper mining industrialist W.A. Clark